Pumpaj! – Serbian protests, strikes, and comics

By Dragana Radanović and Guido van Hengel

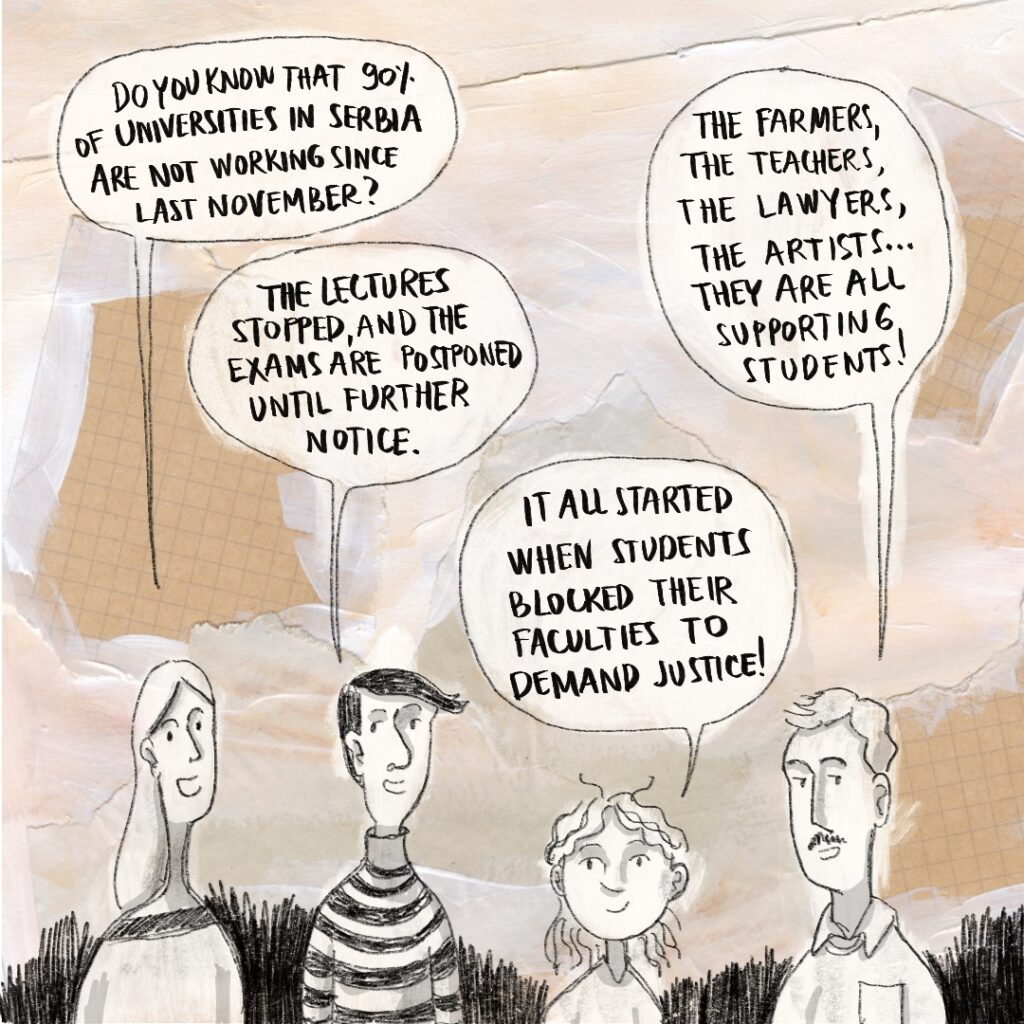

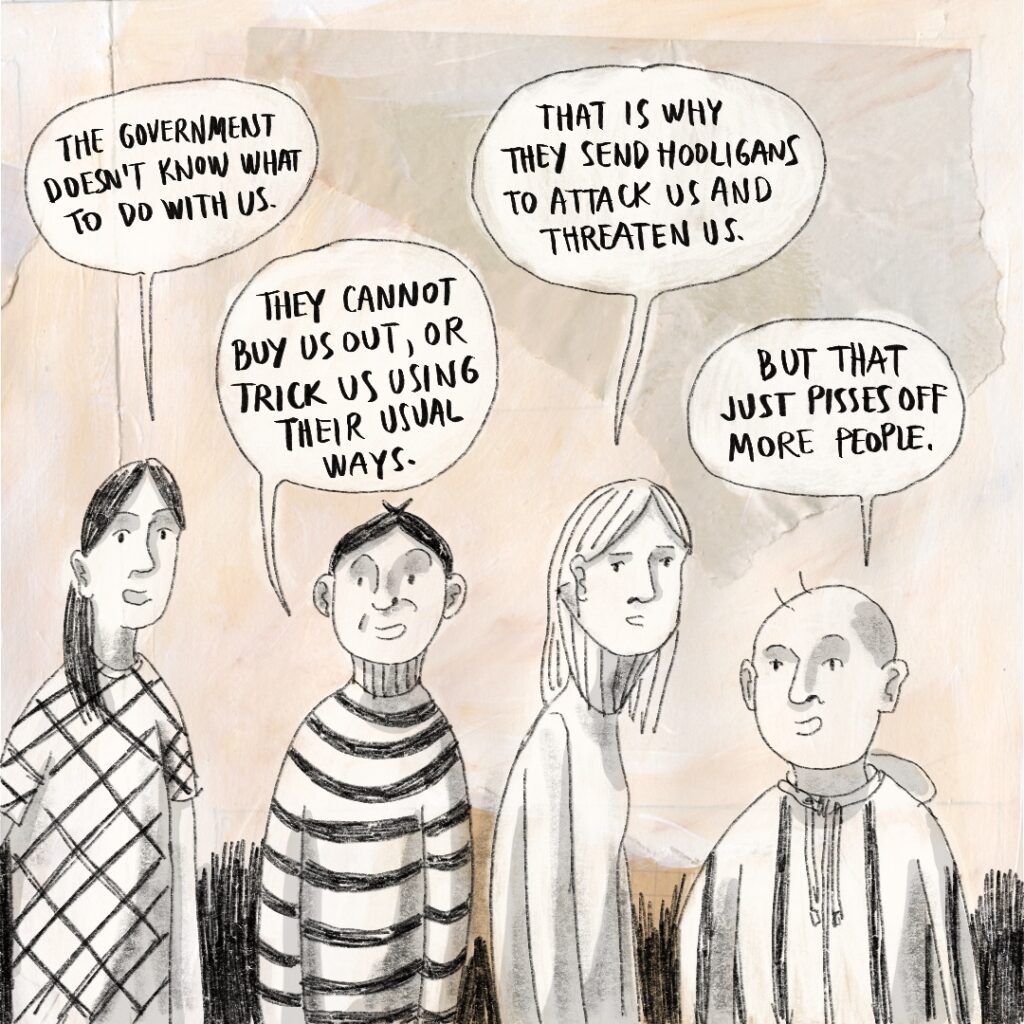

In November 2024, part of the roof structure collapsed at the train station in Novi Sad (Serbia). The causes were linked to corruption and shady construction deals with Chinese production companies. In the weeks and months that followed, students held vigils to commemorate the sixteen victims. These vigils were accompanied by demonstrations and protests, which soon became about much more than just the train station disaster — they targeted the endemic corruption of Serbia’s ruling class, particularly the Vučić regime.

And although protests have been taking place in Serbia for decades, these protests are different. First and foremost, young people (students, pupils) play a leading role in engaging and mobilizing the movement. There is also ample room for creative and peaceful protest, with playfulness, honesty, and humor playing a central role in a movement that remains highly active to this very day. On June 28, a few ten thousands of people gathered in Belgrade to speak out against the corruption and autocratic and undemocratic developments in Serbia.

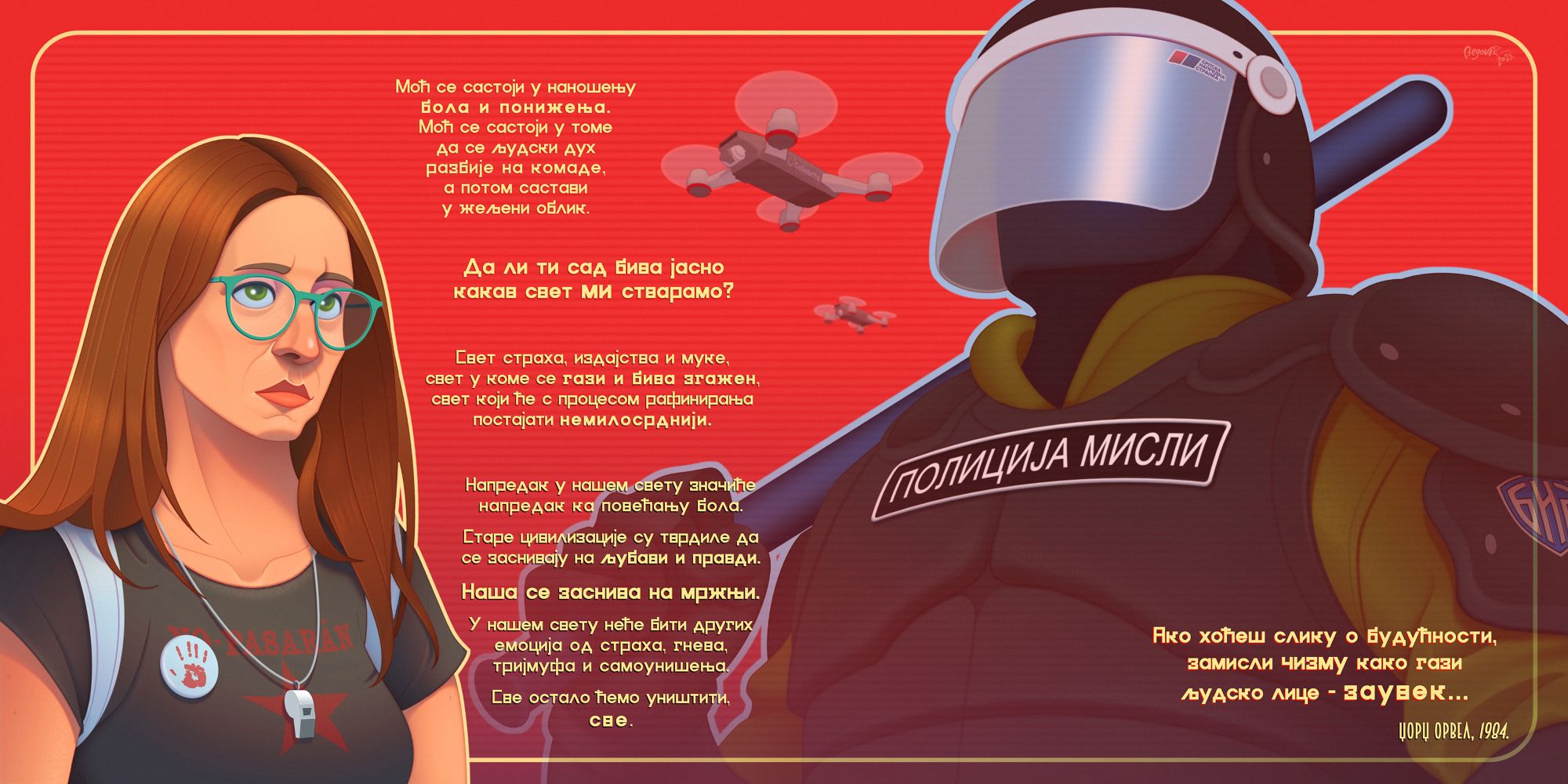

What began in response to tragedy has grown into a widespread uprising against an authoritarian regime that has, for over a decade, eroded public institutions and normalized corruption, censorship, and violence. Nevertheless, artists have mobilized—not just to witness, but to participate. Drawing became resistance. Illustration became testimony. Zines, prints, badges, and comics became tools for solidarity and revolt.

In what follows we highlight some of the responses and reflections we received from Serbian comics writers and cartoonists.

Free speech in Serbia (Jana Adamović)

Jana Adamović reflects on a decade of decline—and what it means to raise a child in the midst of it:

“In Serbia, we’ve been witnessing the steady and dramatic decline of our standards of living, rule of law and freedoms in the last 10 plus years. At the same time, corruption, control, crime and violence have been growing like a cancer. People have had enough and they are showing it in the streets. I only regret it took a whole decade for the majority of Serbia to wake up and stand up. Coincidentally, the last 11 years I have also been a mom. As a parent, I am horrified with the police and state violence and repression. How do you raise a child to be a normal and responsible adult, when all around growing up they see abuse of power and institutions that should protect them? This is my main question and inspiration.”

Dragana Radanović felt called to draw the protests immediately—something that hadn’t happened before:

“These protests were the first protests that made me instantly draw about them. There was a lot of anger, fear, and pain about what happened and, for me, drawing about it was the only way I could deal with my emotions. These protests are different because they gathered everyone, and with every step were bringing small victories. There is something in the way students handled every situation that made me have hope for the first time.”

“Artistic creations about protests are good for spreading the word about what is happening. As someone who lives in Belgium, some of my drawings were a way to share with the international community about protests. We also had images and visuals that became very popular and were motivating people to get out on the streets. They help people share their own feelings and thoughts online, because these visual representations are capturing the essence of what people see, feel and think these days.”

But for some artists, the political and emotional weight made drawing impossible—at first.

El Jakk shared how he lost and regained the will to draw:

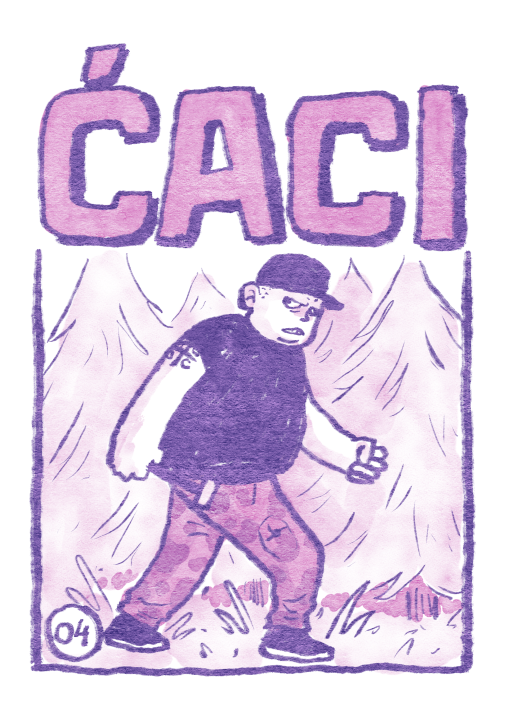

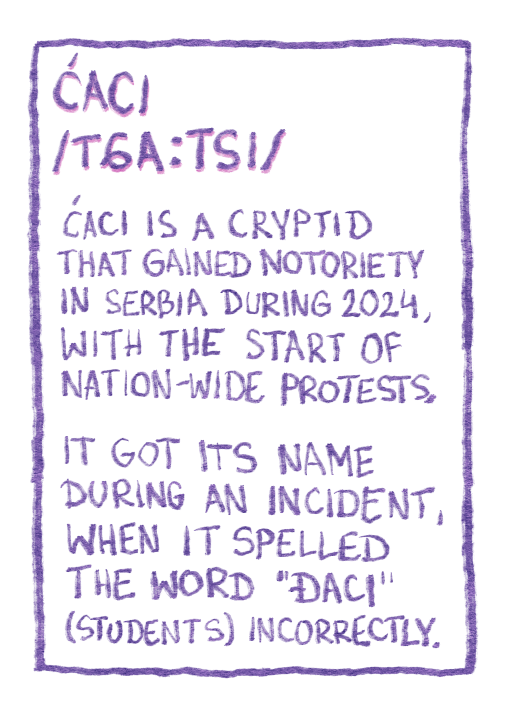

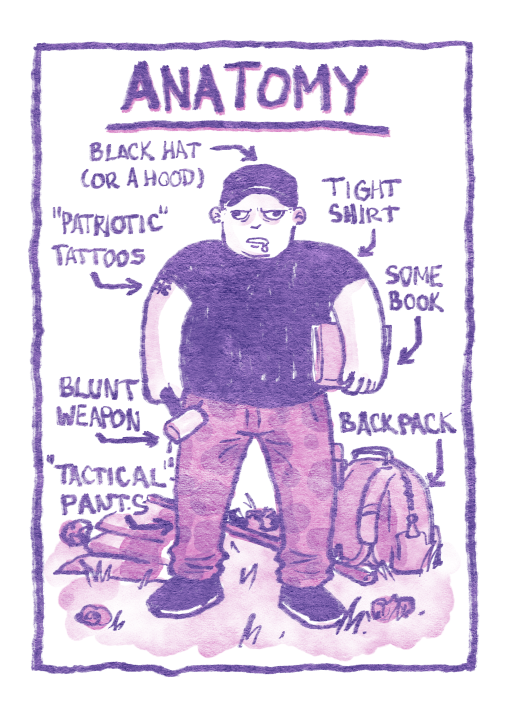

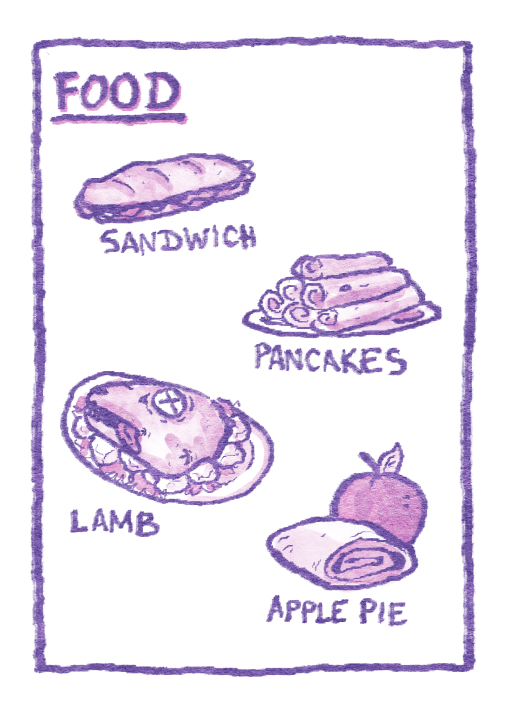

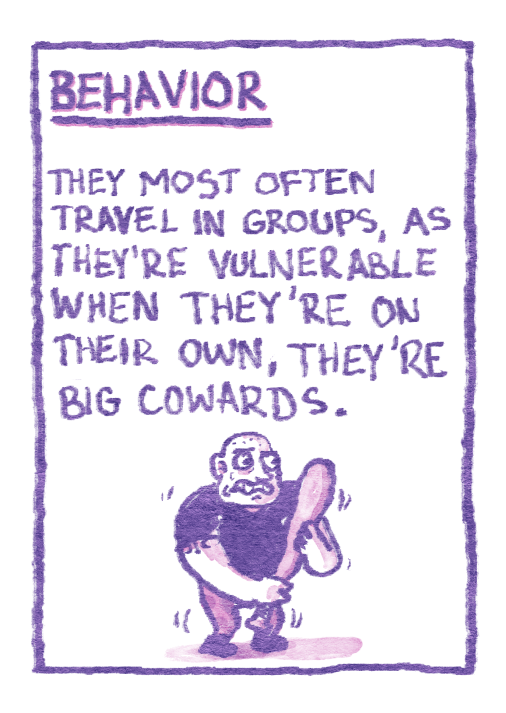

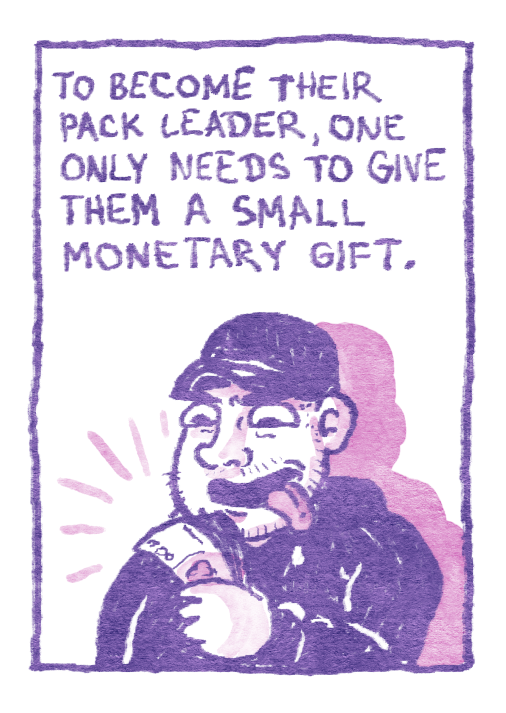

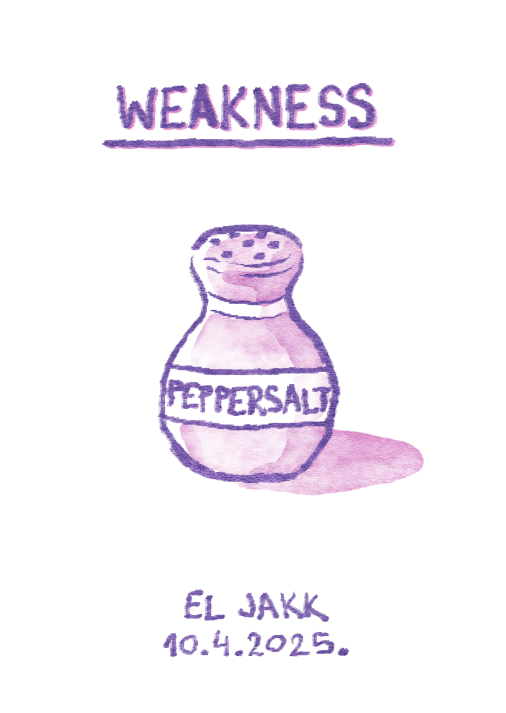

“The collapse of the canopy, and the mix of grief and anger that followed, made me lose the will to draw. Honestly, drawing felt meaningless at that moment—taking to the streets was the priority. As the political situation in the country deteriorated and repression intensified, my mental health worsened as well. Protesting wasn’t enough of an outlet to release everything I was feeling—I had to try drawing again, even though I truly wasn’t in the right state to do it. Since my work is mostly comedic, I attempted to analyze Vučić’s ‘Loyalists’ in a zine format, portraying them like wild animals in a nature documentary.

I also wanted to use illustration to explain to my followers why my comic series has been on pause since November. The characters from my comic Drakče have been part of the protests from the very beginning, and are now engaging in civil disobedience, blocking streets alongside others who are fighting for a better future in this country.”

Biljana Mihajlović uses the art of illustration to reclaim symbols and language, turning slander into beauty:

“The Flower Revolutionary emerged as an act of revolt and defiance against the controversial statement made by Patriarch Porfirije. After meeting with the Russian President Vladimir Putin, he declared that a ‘color revolution’ was underway in Serbia, clearly echoing the views of the ruling regime and insulting students and all of us who have been in the streets for months. In doing so, the Patriarch reduced himself to an associate of President Vučić. The illustration, featuring pumpkins with flowers in their hair, transforms this slander into a symbol of beauty and pride. This illustration was printed on badges which were sold at charity bazaars to collect aid for students in blockades.”

Biljana’s illustrated texts draw from folk tradition and protest slang alike:

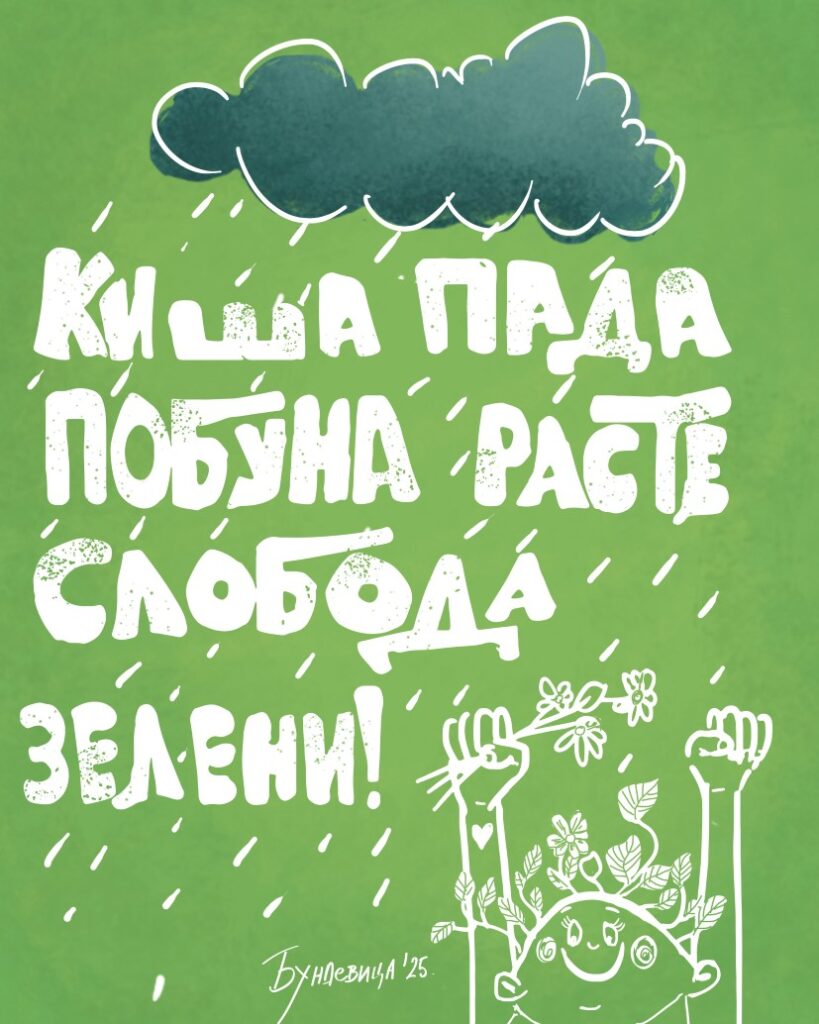

“Freedom Greens is an illustrated text created to support students who have shown great perseverance in their struggle, especially during their marches through Serbia, often in rain and wind. And just as plants flourish under the rain, so does the freedom they bring us.”

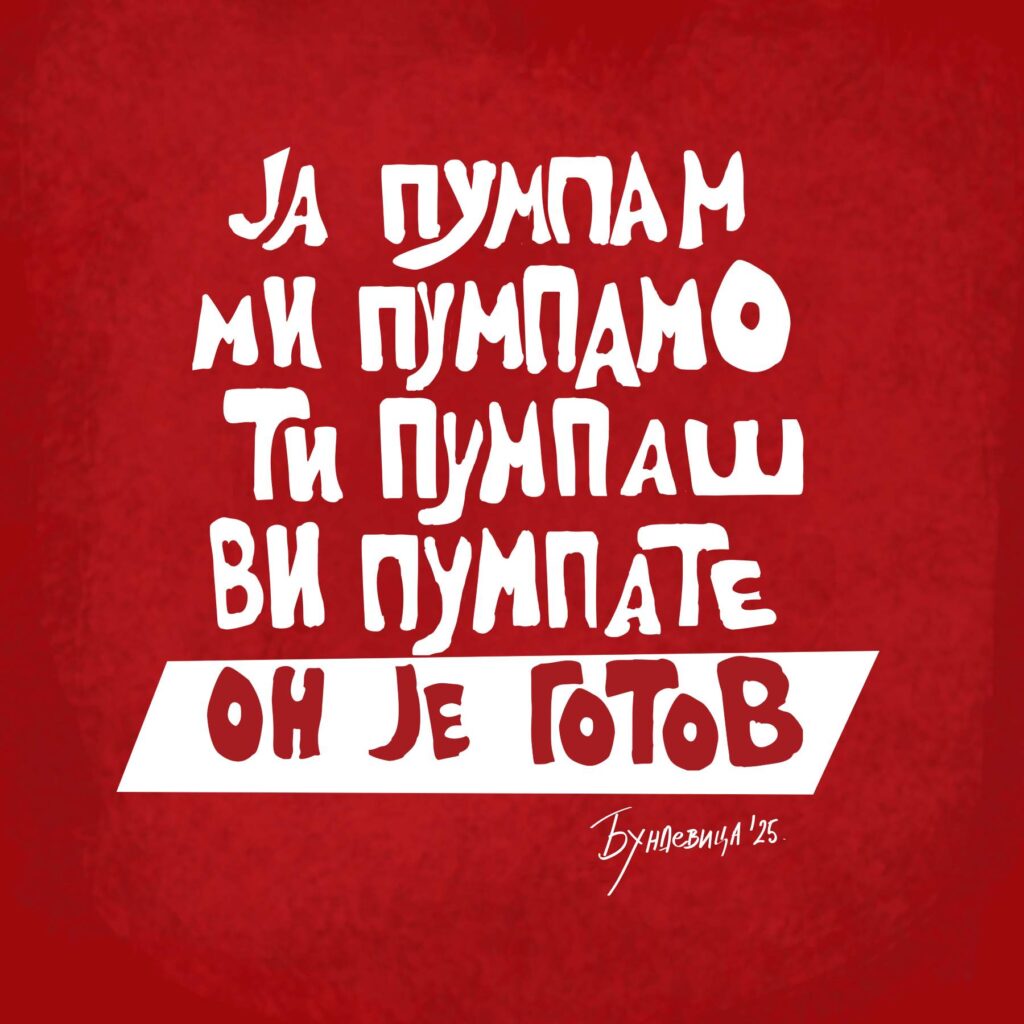

It’s Over is an illustrated text created before the large Vidovdan protest in Slavija square in Belgrade.

“The infinitive of the verb pumpati (to pump it) transformed into the present tense Pumpaj! (Pump it!) has been a symbol and hallmark of the protests from the very beginning. The expression transitioned from internet humor to a powerful symbol of street resistance. Pumpaj has become a synonym of struggle, a message that one must not stop, feel weary, or accept defeat. Victory is inevitable if we all fight together, hence the change in the verb’s conjugation across persons; it symbolizes that we are all in this together.”

Uroš Begović responds through music—creating stark black-and-white illustrations from decades-old rock lyrics that suddenly feel current again:

“When the first wave of student protests began, and we were suddenly confronted—after a long period of hopelessness—with such a surge of youth, kindness, beauty, spirit, energy, and creativity, a wave of inspiration came over me, along with the desire to offer support. A fitting soundtrack to these events often came in the form of local songs with lyrics that felt more relevant than ever, many of which were written decades ago. My love for drawing and rock ‘n’ roll, and the wish to contribute, came together in a series of illustrations as a symbolic gesture of support for the students, high schoolers, and everyone who stood behind them.”

His second series portrays everyday heroes of the movement, such as Marija Vasić (see below).

Maja Veselinović, who has been active in the grassroots initiative Ustala je Ustanička, captures the whirlwind of daily resistance in word and image:

“You’ll see, there’s a bit of everything here—from the beginning of the protests up to now—including one piece from the 2023 protests, the one with the walking figure and the slogan ‘Let’s go,’ which, of course, is still very much relevant. The rest were created over the past seven or eight months as spontaneous reactions to everyday events and the slogans and actions that were current at the time—like Pump it, Sauté it, and so on. There’s also Revolution in Color and Only Love as more general responses to everything that’s been going on.

Since I became actively involved in the work and activities of the local community, specifically the (currently) informal civic initiative Ustala je Ustanička, it also happened that I began selling my works—badges, tote bags, prints, etc.—at humanitarian bazaars that our initiative organized or participated in, where all the proceeds went to support the students. And of course, I wasn’t the only one. For example, at one of the bazaars, Bilja Mihajlović and Daniela Vukov Rus also joined in with their works.

I’m not sure what else to say—this whole struggle is a whirlwind of emotions, terrifying and beautiful at the same time. Terrifying because of the uncertainty, the anger, the violence… but beautiful because you realize you’re surrounded by a community that cares, because you meet incredible people you didn’t even know existed, because of the solidarity, and the small everyday victories that come from being together.”

And then she adds:

“Maybe one day we, the artists who unexpectedly became activists, should sit down and talk about what our lives have been like these past months. What it’s like to panic all morning because you’re way behind on three deadlines (meaning: no money, since illustrators mostly work freelance), and then, from noon onwards, you’re drawing a new badge design or preparing a social media post for the evening blockade in Ustanička Street—entirely voluntarily, because that’s just what feels right.

You simply can’t pretend things are normal and tune out. You fight to maintain balance—professionally and personally—to channel your rage, direct your love, and stay true to yourself…”

This is not just a story of art. It is a story of refusal. Of artists choosing to speak when silence felt unbearable. These drawings, zines, badges, songs, and slogans—made in living rooms, shared on social media, sold at bazaars—aren’t just artistic reactions. They are the movement. They hold the memory of what it felt like to stand up, speak out, and hope—together.